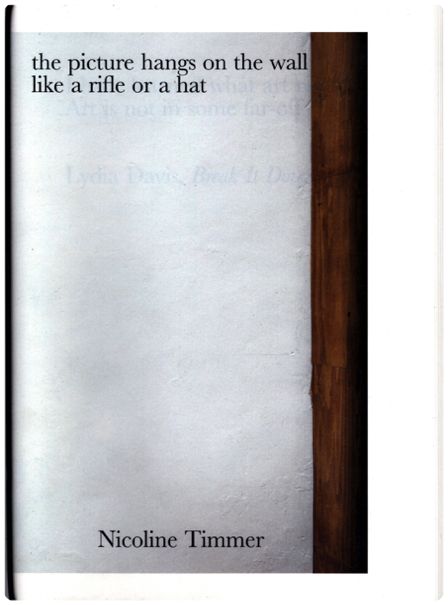

the picture hangs on the wall like a rifle or a hat

- 2011 -

publication

works & text Nicoline Timmer

graphic design Esther Willering

photography René Bosch

THE PICTURE HANGS ON THE WALL LIKE A RIFLE OR A HAT is an investigation into finding a ‘place’ for my work. Does a sculpture or a video, an installation or a book take place somewhere?

*

The Shakers, an American religious sect founded at the end of the eighteenth century, excelled in craftsmanship. ‘I almost expect to be remembered as a chair or a table’, Sister Mildred from Sabbathday Lake once remarked. And indeed the Shakers are today mostly known not for their religious beliefs, but for their pure and simple design, such as their wooden ladder-back chairs. (They also, incidentally, invented the clothespin.)

One typical Shaker element is that they aligned all the walls of their dwellings and workshops with pegboards, on which they would hang everything from chairs to brooms to plants to paintings. (Albeit paintings only in the later, less ascetic days of their existence...) It was a purely functional solution. It allowed them to easily store away an excess of chairs if, for example, their meetings were attended by less people than they could (or would want to) accommodate. A carpenter could hang his tools on these pegs, or his hat, and a seamstress a sample of fabrics.

The simple functionality of this pegboard, of always having a place for your things, has an enormous appeal to me. Also the fact that the pegboard is very indiscriminate (in a good way). There is equal room for every thing.

It doesn’t single any thing out as extra special.

Against the background of my interest in finding (or creating) a right habitat for my works, the pegboard offered itself as a possibility, as a potential ‘somewhere’ to temporarily store my works, or certain elements of them. In the process of presenting them this way, rearranging them and letting the works interact with related objects and tools, the works change, take on a new identity, because what is presented is different from how they were ‘originally’.

The diffuse practicality of using a pegboard to present my work, reminded me of a sentence that has nestled in my mind and that I had once underlined in an essay Heidegger wrote called ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’. I decided to use this sentence as the title of this book.

For me Heidegger’s essay is about trying to distinguish works of art from daily objects, and from what he labels ‘equipment’, tools. Works of art are (usually) things – but special things, we would like to say. The question is: special how? The answer today would probably sound very different than the solution Heidegger came up with around the end of the 1930s...

Arthur Danto gives it another try, at around 1980, long after the readymade had entered the domain of art, in a chapter with the salient title: ‘Works of Art and Mere Real Things’. Danto raises the question ‘why this breadbasket is a work of art [a breadbasket he lets a fictive artist named ‘J.’ exhibit] and the one on my breakfast table is not’. It’s not a matter of form, not a matter of intention, not even a matter of attitude, he feels. But what then?

I am less interested in knowing the answer to this question, than in exploring this shifting border between the things or objects surrounding me in my world, the tools with which I create order or disorder in this world, and the works I make.

Sometimes for me the making of a work is the work, which would mean that the drill and hammer, or the sewing machine and scissors, used during the work process, are inherently part of the work. Or perhaps these tools are not actually part of the work (it depends on how you look at it), but exist just at the limit of the work.

And sometimes for me the presentation of a work becomes the work, or becomes a new work. (It’s hard to tell.) Choices are made, a certain perspective is introduced, and things are temporarily fixed in a complex of relations.

I believe a work can incorporate divergent elements (and expel them also) at different times, so that the limits are never completely fixed. The identity (or ‘meaning’) of a work can therefore morph over time. This is a good thing. It creates room for thinking new thoughts, for establishing new relations.

If a person steps on my work, he or she becomes part of the work (as in the case of the quilts I made, which were lying chameleonically on the floor of the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam).

If I iron my work (again, with the quilts), let’s say twenty minutes before people will come and have a look, the moment of ironing can become more significant than the actual exhibiting of the work, when the work is supposedly ‘finished’.

If you turn a work inside out, it may be more itself than when shown at its best behaviour.

Or maybe you only need part of it, of the work.

Or a picture of it.

Or just the memory of it.

Or a description.

And maybe some works belong in an attic, a closet, or shady storeroom, and being pinned to a white gallery wall is not at all their natural habitat.

We cannot ask them.

We can only try out finding a right place for them, if only temporarily. Bring them in contact with what surrounds them. Create room for thinking new thoughts, for establishing new relations.

This book has been an attempt to do just that.

a re-presentation of the work BAF ! (2009)

a re-presentation of the work QUILT OF THE STUDIO (2009)

a re-presentation of the work SOMETIMES I ALMOST EXPECT TO BE REMEMBERED AS A FLOOR (2011)

a re-presentation of the work READING THE NEWSPAPER (2011)